What if people choose not to participate?

By Joan Cody, RN

My father, along with millions of others of his day, fought in World War II to protect a way of life. He came home with a number of medals, and went on to live that good life. He married my mother and had three children. He worked hard and was a good provider, a loving husband and wonderful father. He passed away many years ago, far too early for those whose lives he touched. I remember him in many ways, in particular as a war hero. And because of him, whenever there is an election—whether local, provincial or federal—I encourage everyone to exercise their right to vote. The right to choice and participation is a hard-won battle that continues around the world today. “Use it! Don’t take it for granted,” I remind everyone. But what happens when individuals cannot—or choose not to—be involved? Can we ensure democracy if we fail to have participation?

The role of a resident and family council

The goal and vision of Resident and Family Councils in residential health care settings is to promote the quality of life of the home’s residents. Commitments to residents ensure the ability to establish resident organizations and the freedom to express concerns, comments and suggestions. Terms of reference indicate the ability to be an autonomous, democratic group, and the administration’s support for this. These Councils offer residents the chance to participate as individuals, with family, friends and facility staff available to assist with information when needed. Residents meet to share common interests, learn new things and have a forum to voice concerns and suggestions.

I have had the pleasure of working with such Councils for more than 20 years. Some have been more active than others, and their roles have been as diverse as the individuals who joined them. Some, for example, have focused on fundraising for activities and outings; a few were interested in policy, practice and decision making; and many more were concerned with the smaller sphere of topics that directly impact their lives.

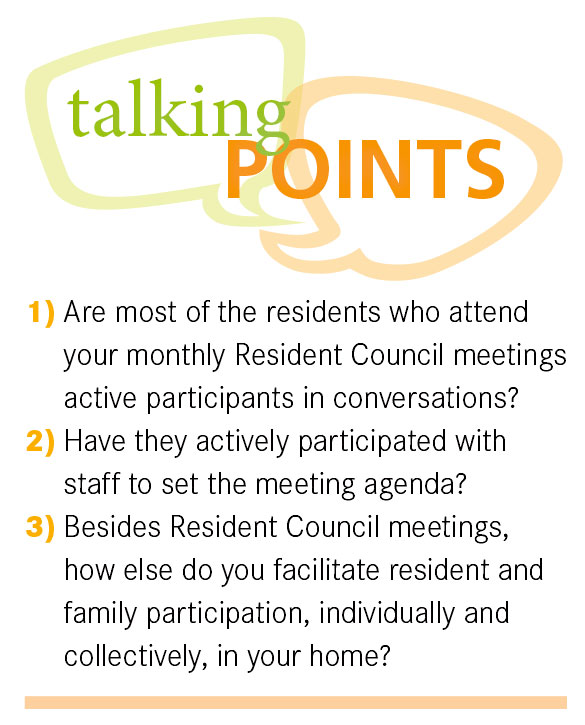

Council meetings generally provide a time to ask whether there are any concerns about the quality of meals, the variety of activities offered, and the kindness and compassion of staff. In our home, our monthly meetings have enabled us to work through the decision to play country music rather than contemporary music at lunchtime, to have a local news channel on TV after supper as opposed to The National, and to name our homes Cat ‘Boots.’ These might seem like small things, but they have been choices and they have been important to our residents. We have always had a chairperson, a treasurer and staff members to assist residents in the facilitation of the meeting, and we invite families to join us. It sounds like a great thing. It sounds like something residents and their families would want to attend, participate in and champion. It sounds like the right thing to do. But recently—for the first time in over 20 years—we held our monthly meeting, and no one came.

Council meetings generally provide a time to ask whether there are any concerns about the quality of meals, the variety of activities offered, and the kindness and compassion of staff. In our home, our monthly meetings have enabled us to work through the decision to play country music rather than contemporary music at lunchtime, to have a local news channel on TV after supper as opposed to The National, and to name our homes Cat ‘Boots.’ These might seem like small things, but they have been choices and they have been important to our residents. We have always had a chairperson, a treasurer and staff members to assist residents in the facilitation of the meeting, and we invite families to join us. It sounds like a great thing. It sounds like something residents and their families would want to attend, participate in and champion. It sounds like the right thing to do. But recently—for the first time in over 20 years—we held our monthly meeting, and no one came.

It made me wonder whether meeting attendance, engagement and participation were good gauges in ensuring resident and family choice has been supported. How can we continue to guarantee that individuals and the collective are heard, while acknowledging and accepting the reasons and barriers that may prevent people from becoming (and staying) involved? In fighting the battle to be inclusive, we must also be mindful that choice includes the right to choose to decline. The right to be silent, the right to trust others to make decisions for you, the right to choose not to go to a meeting.

Plenty of reasons for non-involvement

During our recent attempt to engage residents, I listened to the many reasons residents and their family members gave for not coming to Council meetings. Some told me their days of committee involvement were thankfully done. Others said they were too tired to attend something that had little to do with them. I was told that it was my job to take care of the money now, that I was trusted to look after their best interests, and that I did not need them getting in the way. One person noted that no one would like their ideas and doubted that they could contribute in any significant way. A few said they would not like what others had to say, and admitted that others might not like what they had to say either. One resident told me not to bother asking her daughter about the food. “What would she know; she eats sushi,” she told me. A large number of residents have dementia and so lack the capacity to participate in a discussion about the benefits of a Resident Council. Some family members told me that the beauty of a good continuing care home was the feeling that a burden had been lifted from them, that their loved one’s needs were being met and that they could now stop organizing and deciding and fixing problems—so they did not want to participate, thank you.

Encouraging participation

It is very important to help residents and families understand the benefits to them, both individually and collectively, of being involved in Resident and Family Councils. These Councils do impact the quality of life of a home’s residents. They do serve their mandate and should be offered, available and facilitated when the residents of a facility and their families choose to have one. Nevertheless, while many jurisdictions mandate that facilities have councils, they may fail to recognize that it is equally important to recognize that a resident’s day-to-day activities of life and their personal choices, and perhaps the limitations caused by a myriad of health issues, may mean that some simply choose not to participate. Consequently, when residents decide not

to participate in Resident Councils, individually or collectively, those decisions must be respected as an exercise of real and meaningful choice. We must ask ourselves if it is always necessary to exercise our democratic right. Is there a time when it is okay to entrust decision making to others? Can we accept the idea that sometimes people are just tired of being engaged?

There is a great deal of literature and many tools to assist facilities with the development of admirable Resident Councils; however, it is increasingly and equally essential to establish mechanisms and supports to ensure our residents’ voices continue to be heard outside of these traditional means. How will we teach ourselves and our staff about the influence and worth of our role as the voice of our residents? And, as with all moral decisions related to autonomy, we will need to be especially mindful of making decisions that truly reflect what our residents would choose to do if they could or wished to do so, not what we would choose to do if we were in their circumstances.

Joan Cody, RN, is ethics practice leader at Extendicare (Canada) Inc.