A look into GPS use for home care clients with dementia

By Tracy Raadik-Ruptash

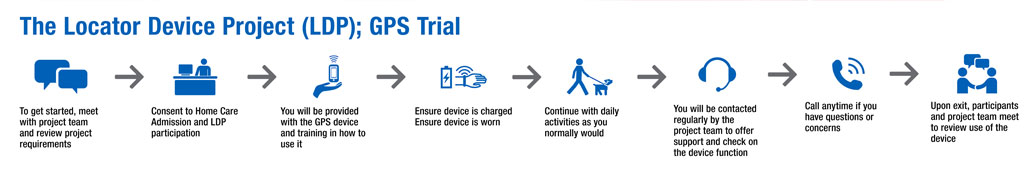

Dementia symptoms can be a challenge for both the patient as well as their caregivers. The risks are real and can be devastating. The Locator Device Project (LDP) is a research project grant funded by Alberta Innovation and Advanced Education (IAE) being conducted by Alberta Health Services (AHS) in partnership with key Alberta stakeholders. AHS continues to be client-focused and try new ways to support continuing care clients to age in place and stay in their community-based homes. The LDP is looking to see if using wearable GPS-enabled devices will help people with dementia who are at risk for wandering.

The number of people with cognitive impairment is growing quickly in Canada. This fast growth is due, in large part, to our aging population. People with cognitive impairment can have many symptoms, one of which may be wandering (impaired way-finding). Because wandering behaviours can happen for many reasons they can be difficult to manage. No matter what the reason, when this happens, their safety is compromised. Because of the huge safety risk and the trouble managing these wandering behaviours, the person with the cognitive impairment often loses his or her independence, increasing the burden on the caregiver. Locator technologies—such as global position system (GPS) technology—may be an effective strategy to decrease risk associated with becoming lost. This is because the person’s geographic location can be monitored while at the same time maintaining the person’s autonomy.

The Alzheimer Society of Canada estimates that about 747,000 Canadians have dementia. In 2010, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) reported that 1in 4 Canadians over the age of 65 had an age-related cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Up to 63% of seniors with dementia who are still living in the community have had issues with wandering (Hogan, 2004).

Ethical considerations are of foremost concern during project planning, approval and device trial. The LDP is ethics board approved and utilizes participant consent and assent. Participant dyads (Home Care clients and their family caregiver) are recruited to take part in the technology trial: The GPS technology is programmed to maintain confidentiality by reporting to family caregiver(s).

GPS Technology

The wearable GPS technologies include features that can be programmed for the user. Some of these features include:

• Two-way voice communication

• Panic button for direct family contact

• Geofencing

• Single button push dialing

• Automated notifications by text and email

• Breadcrumb trail

• Real time location

Four wearable GPS-enabled devices are being trialed. These include cellphone like hand-held devices that can be worn in a lanyard, carried in a pocket or purse, a watch and insoles that can be placed within walking shoes. To best protect the privacy and wishes of the people in our study, the technology trial is designed to report to family only. The software and website can only be accessed by password by family caregiver(s).

Using GPS-enabled devices, the users carry on with their usual routine. However, if the person travels off-path, wanders, or becomes lost, the GPS-enabled devices allow for additional support by alerting a family caregiver. The family caregiver can access the secure website to find out where the user is so they can respond accordingly. Real time map access is available through a smartphone app, or mobile website in addition to website access from any internet connected PC or laptop. Using these tools, the family caregiver can track or find the device user and help them as needed.

The devices also provide a breadcrumb trail of the path the person is on. This can be helpful if the device enters a large structure where the signal may be blocked or if the device loses battery power. If this happens, the last known location of the device is always recorded.

How can GPS help support client independence?

Fern’s Story

Fern is 90 years of age and lives alone with the support of her son and daughter-in-law. She still manages many of her own Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs) such as simple meal preparation, taking her medications and even some grocery shopping. Fern is an avid walker in the area around her home; she is regularly visiting the neighbourhood pharmacy and grocery store. Fern can become confused and disoriented when she is unwell, exacerbating her dementia diagnosis.

Given her age, family members were concerned about how receptive Fern might feel about wearing a GPS device. It was surprising to see how accepting of the device she was. She accepted it without hesitation and she wears it regularly; every day on a lanyard around her neck. Fern has even learned to charge the device herself. She has established a routine of charging the device every night and wearing it every day. Having use of the GPS device brings feelings of extra safety and security to Fern to know she has the device to easily link her to her family. She trusts that should anything go wrong, they will be there for her.

Fern has a geofence set up around the perimeter of her neighbourhood and includes her home, typical walking routes, and the shops that she typically visits. Sometimes, Fern also likes to visit the shopping mall, which is a greater distance from her home and is located outside of the geofence. To get to the mall, Fern uses public transportation. When Fern travels to the mall on the bus and exits the home-geofence perimeter, her son, Dan, is sent an automatic alert notification by email and /or text.

When Dan receives this automatic notification information, it includes a map plotting Fern’s location and he can see from this information that Fern is on route to the mall. If he gets a second alert later in the day that tells him Fern has entered her geofence, he can see that she has used the bus to return home again.

But, if he does not receive a later alert, or decides to check on Fern, he can see where she is on the software map. If this occurs, usually he will find that she is still at the mall, and when his workday is done, Dan will swing by the food court to pick her up and take her home.

Sue’s Story

Sue wants to maintain her mobility and independence as long as possible in light of her dementia diagnosis. She loves to walk her dogs around the neighborhood she has lived in for 20 years. But there have been times when Sue has become disoriented on a routine walk and had trouble finding her way home again.

For Sue’s spouse, Ken, it is challenging to honour Sue’s wishes and also manage the threat posed by her memory impairment. Should Sue encounter difficulty in finding her way home, not knowing specifically where she had travelled to, or what direction she had chosen to go, it was very stressful for Ken, and trying to find her when she had been missing was an experience he would never want to repeat.

Like many resourceful families we know, this couple has tried common commercial solutions like having Sue carry a cellphone on walks. Limitations to this were that the cellphone became too complicated for Sue to use and eventually it went missing. After that, they purchased a GPS device, but it was lost in time as well. What appealed to them about the LDP was that the GPS device could be secured and may therefore be less likely to go missing.

Now, Sue does not go out for a walk without her GPS watch and she is pleased to wear it. With the watch on, she can enjoy walking her dogs with the security of knowing that she has a safety net: If she is gone too long the means are in place to allow Ken to find her through the associated software. If she recognizes that she has gone off path, she can contact Ken by using the panic button.

Back home, Ken can observe her walking route by using his smartphone, and if necessary, he can take it with him to easily find her and assist her in returning home. The technology brings Ken great peace of mind. Especially with the winter weather, there is less risk of Sue being missing and stranded outside for long periods of time should she get off path.

How can GPS help manage caregiver stress?

Mr. Smith’s Story

Before trialing the GPS device, Mr. Smith had been missing several times. Police services were often called in for assistance in finding him. Mr. Smith is easily over stimulated or upset and will seek to escape the situation: He will leave the house. Mr. Smith does not live too far from the family farm where he grew up. So when he becomes upset, typically, he will walk his way toward the old homestead. This can happen as frequently as three or four times per week.

With use of the GPS device, the software sends an alert to Mrs. Smith’s smartphone each time he leaves the geofence. So, even if she is unaware that he has gone walking toward the farm, the notification finds her. She then has the ability to check his path of travel. If he is on his way to the farm, she will often give him time to walk; this calms him. Mrs. Smith can use her smartphone to check his current location, locate him with ease and return him safely home when it is time to assist him in returning home.

There are often times when Mr. Smith has not been on path to the farm and will go walking in a random direction or alternate route than usual. These occurrences are no longer as stressful as they used to be because Mrs. Smith can locate him wherever he may be and assist him safely home.

There are many considerations for users in determining whether locating technology is a match to user needs. For information on considering GPS device use for those with dementia diagnoses, visit the Alzheimer Society of Canada and search Locating Devices.

The LDP will be completed for Steering Committee review following summer 2015.

Adapted from a presentation by Tracy Raadik-Ruptash, BScOT, OT (C), Project Lead, Alberta Health Services, provided on November 4, 2014 at the 2014 Canadian Home Care Association Summit held in Banff, Alberta

Tracy Raadik-Ruptash is a Project Lead with Health Technology Assessment and Innovation, Alberta Health Services. Building upon extensive Home Care experience, her recent years have been focused on leading innovation projects.