Learning from those who have lived it:

The perspective of a survivor of a traumatic brain injury

By Rhona Anderson and Steve Gregory

Two hallmark concepts that health care professionals who work in rehabilitation would likely agree are the foundations of the rehabilitation process are: engaging clients in the rehabilitation process; and focusing on interventions that lead to functional outcomes. Rehabilitation professionals are evidence-based practitioners. Evidence is viewed broadly, however, and includes not only the results of research studies from peer-reviewed journals, but also clinician experience/expertise and client perspectives of what services reflect their interests, values, needs and choices.

Two hallmark concepts that health care professionals who work in rehabilitation would likely agree are the foundations of the rehabilitation process are: engaging clients in the rehabilitation process; and focusing on interventions that lead to functional outcomes. Rehabilitation professionals are evidence-based practitioners. Evidence is viewed broadly, however, and includes not only the results of research studies from peer-reviewed journals, but also clinician experience/expertise and client perspectives of what services reflect their interests, values, needs and choices.

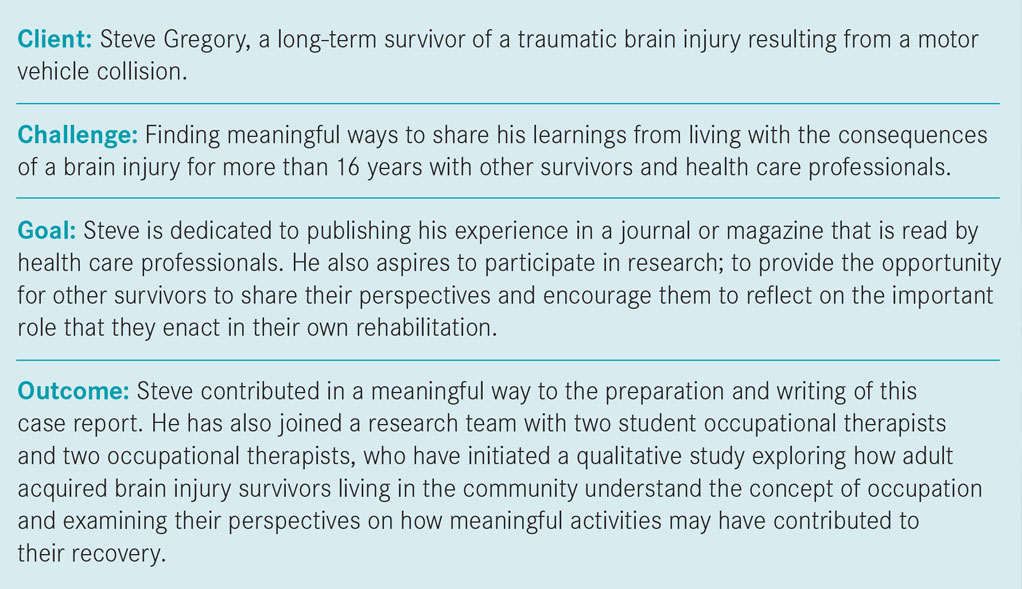

The purpose of this case report is to bring together these ideas by highlighting the perspectives of Steve Gregory, a long-term survivor of a traumatic brain injury. His views relate to how best to engage clients in the rehabilitation process by using strengths-based approaches. He also emphasizes the importance of engaging clients in therapeutic activities of daily living, not just for the end purpose of gaining functional abilities, but also for the therapeutic value of using meaningful activities (occupations) as a way of providing therapy.

Steve’s history

Steve’s history

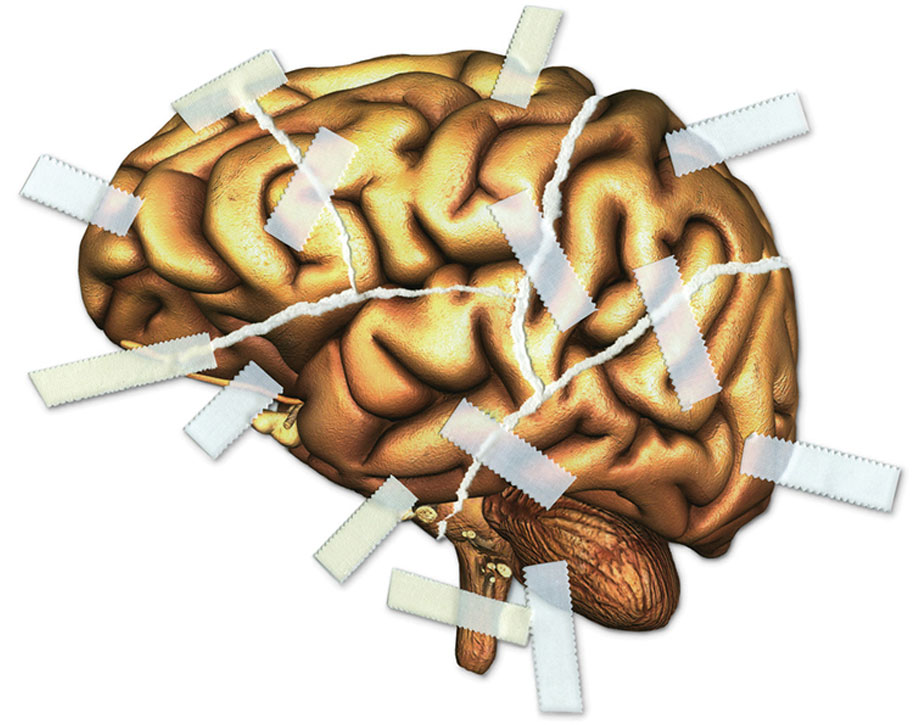

Steve sustained a severe brain injury as a result of a motor vehicle collision in 1999. His insurance company became involved and he entered the medico-legal system. He was deemed catastrophic by the designated assessment centre while still in the hospital (scoring 3 on the Glasgow Coma Scale). The health care team identified dysarthria, ataxia and diplopia during the initial rehabilitation process. (While these impairments are still challenging to Steve, they have abated to some extent and do not prevent his involvement in many meaningful activities.)

While in hospital, Steve was bored by the lack of activity. He felt this way for most of his rehabilitation, as there was simply not enough going on to satisfy his drive. Steve’s perspective on his entire rehabilitation experience is not entirely positive. His boredom or disengagement might have been related to his view that the health care professionals did a deficit-based analysis of his skills, rather than a strengths-based assessment. After a thorough assessment of his dysarthria, ataxia and diplopia, Steve was eventually told that he would never go back to any sort of paid employment. He wondered what the future would bring and what would give meaning to his daily life.

Strengths-based approaches

Steve now advocates that health care professionals use strengths-based approaches with their clients. Strengths-based assessments are gaining recognition in some professions (e.g. social work, mental health and children’s educational planning) and with some populations and are compatible with approaches such as coaching and appreciative inquiry, which are used by health professionals both with individuals and in organizational work. Assessing in a way that is strengths-based has been described as “The measurement of those emotional and behavioral skills, competencies and characteristics that create a sense of personal accomplishment, contribute to satisfying relationships with family members, peers…enhance one’s ability to deal with adversity and stress, and promote one’s personal, social…development.”

In relation to Steve, this might have meant highlighting his drive to participate and manage his health and wellness needs; his engineering-focused mind, which was still capable of breaking tasks down and solving problems; and his sense of humour and interest in social interaction.

participate and manage his health and wellness needs; his engineering-focused mind, which was still capable of breaking tasks down and solving problems; and his sense of humour and interest in social interaction.

In any rehabilitation setting, there are challenges to focusing on strengths. The vast majority of assessments gather information about deficits and care needs, and these form the foundation of the rehabilitation plan. Rehabilitation within the medico-legal system is even more complex, as deficits and care needs often form the basis of the legal case for financial compensation. This is an opportunity for rehabilitation professionals to demonstrate their understanding of each client’s complex needs: First, the need for advocacy within the medico-legal system; and second, the need for rehabilitation professionals who offer partnership, hope and assistance in recognizing, cherishing and capitalizing upon the positive.

Steve contends that survivors are survivors for life, and recovery should be recognized as a long-term plan that exceeds the time expected by the medico-legal system. He believes that rehabilitation professionals can help survivors transition from a state of being taught and coached, to one of self-directed learning based on self-knowledge of one’s own strengths and how to capitalize on them. Steve describes this view as a paradigm shift for many rehabilitation professionals, but sees it as imperative in promoting the survivor as being in charge of his or her own therapy.

Meaningful activities

Steve’s second key message concerns the importance of engaging clients in meaningful activities (occupations) as a vehicle for recovery, as well as for the inherent pleasure that comes from doing something that is unique and important to the individual. These concepts are not novel; in fact, the conceptual underpinnings of the profession of occupational therapy are based on the belief that everyday occupations are the foundation for supporting health and well-being. That said, Steve believes that the entire rehabilitation system could improve in its ability to enact that perception.

Steve recalls that it was his brother who gave him a toothbrush early in his hospital stay to encourage his return to performing daily activities, and Steve embraced the experience and started to incorporate similar initiatives into his own recovery. Steve can now cite countless examples of how to grade and structure everyday activities to enhance their therapeutic value. Each set of activities serves multiple purposes related to need, enjoyment and enhancing skill development and recovery; examples include doing the laundry, making meals for the purpose of enjoying and sharing favourite foods, and planning to train for a running race. Steve learned how to be his own best therapist and recommends that rehabilitation professionals guide their own clients to do the same. Steve has even developed his own paradigm on modifying tasks to maximize their therapeutic potential. In his opinion, engaging in daily occupations has enhanced his decision-making skills, ability to process information, understanding of structure and schedules, dividing and alternating attention skills, self-confidence and self-awareness skills, to name a few.

Barriers in the system

Barriers in the system

Again, there are barriers within the health care and medico-legal systems to adopting an individualized, occupation-centred approach to therapy. A primary limitation relates to lack of resources, including time, availability of tools and control over the contextual factors surrounding the therapy.

Here is an example to illustrate these ideas. Imagine that Steve put utmost value on his relationship with his dog, an 80-pound German shepherd and, during his hospital stay, he primarily focused on wanting to be with this dog and care for him again. Excellent specific, measurable and attainable goals could be generated from this aspiration, including feeding the dog, putting him on his leash, taking him for walks, grooming him, driving him to the veterinarian, vacuuming his rugs to pick up dog hair and so on. A good interprofessional team would keep this aspiration and these goals in mind throughout the rehabilitation process with Steve and work through these tasks in practice. These would not necessarily be the typical interventions of the team, and the necessary tools for practice would not be easily available in the hospital. However, the team might use a bag full of beanbags weighing 20 pounds to stand in for a bag of dry food.

Perhaps an even better team would consider how to work through these tasks in the right context with the dog present, as nothing can compare with trying to feed a dog while the 80-pound animal is excited and jumping up to be included. To accomplish this, the health care professionals would likely need to forego some more “typical” assessments or interventions that would be less relevant to Steve, and instead: advocate for Steve to participate in a home assessment that addresses his dog-related goals; communicate with the family member who is caring for the dog and coordinate schedules; collaborate with various team members with knowledge about the related skills for performance; and more. It is easy to see why this route is pursued less often—these are not easy (though not impossible) tasks for an inpatient health care professional. Many skilled competencies of the professional would be used, and experience and confidence would certainly be important assets.

Steve’s development

Steve continues to make gains more than 16 years after his injury. He views his ability to continually improve as unique and important. He points to his faith, his beliefs about strengths-based approaches and his therapeutic use of meaningful activities as being foundational to this ability to improve.

This case report offers Steve’s perspective on how health care professionals can best engage their clients in the rehabilitation process and combine them with a clinician’s experience working with persons with brain injury; a clinician who aims to recognize each client as unique, with strengths to learn about and meaningful occupations to discover and understand.

References available upon request.